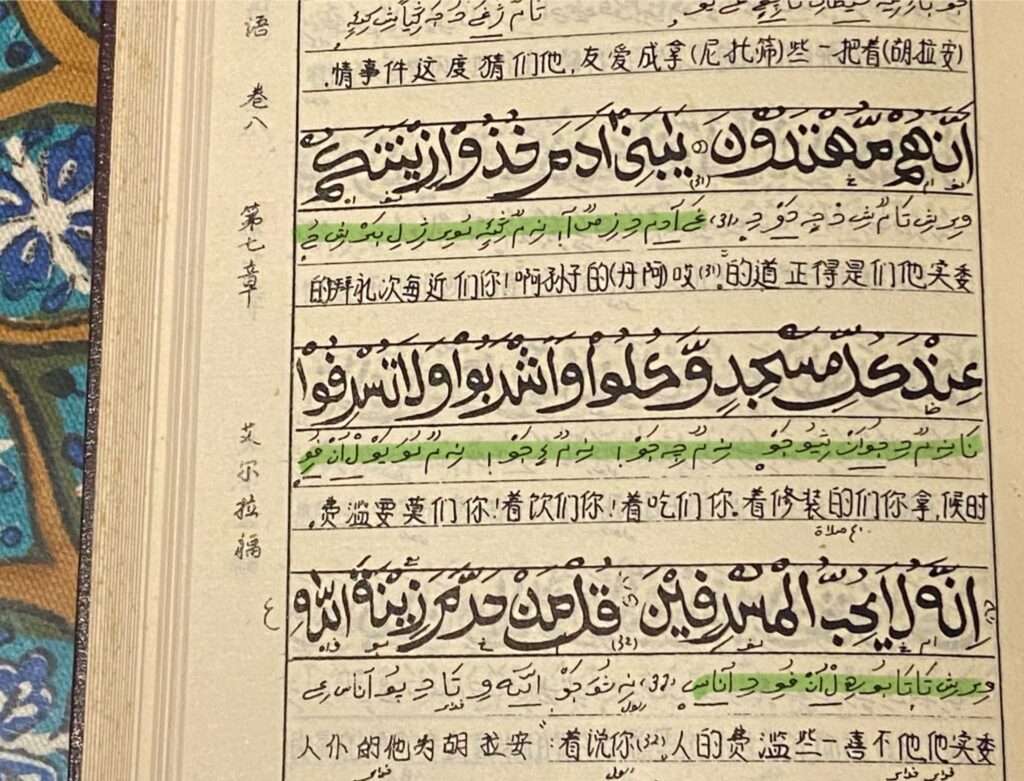

Image Source Iskandar Ding

I have spent the past few months building a tool to transliterate Chinese characters into Perso-Arabic Xiao’erjing script. You can try it here.

This tool is more than just a novelty. China has a long Islamic history that dates back to the Tang Dynasty (618 to 907 CE). Arab and Persian people have migrated to and lived in China via the Silk Road for millennia, bringing with them Islam amongst other faiths and the Perso-Arabic writing system.

These Persians and Arabs assimilated with the native Han Chinese over hundreds of years and became known as the Hui people. The Hui are a Mandarin-speaking and Muslim Chinese ethnic group.

The Hui people attended madrasas to study Classical Arabic and the Quran. With the complexity of Chinese Hanzi characters, these students were much better at speaking Chinese than they were at reading or writing it, so they used Perso-Arabic script instead to take notes in Chinese.

Troubles with Standardization

“Mandarin or Cantonese?” is a common question that Chinese people get asked, but dialects in China are much more complicated than this common question suggests. Mandarin has many regional variants, and it sounds different in the Northwest as compared to the Northeast. Then, as you move south, the people cease to speak Mandarin at all, speaking instead one of several Chinese dialects that are completely unrelated to Mandarin, such as Cantonese or my family’s native Shanghainese.

The Hui Chinese are native Mandarin speakers but they speak regional variants of Mandarin which vary in pronunciation. A Hui person would write Xiao’erjing in accordance to their own regional pronunciation and their interpretation of its transliteration. The variance in pronunciations and transliterations made Xiao’erjing difficult for anyone who wasn’t the writer or the intended recipient to understand.

Another problem with Xiao’erjing to represent Mandarin is that it cannot display the tones present in Mandarin. (Ex. shan1 xi 山西 vs shan3 xi 陕西) In addition, syllable endings are indistinguishable. (Ex. xi an 西安 vs xian 仙)

Because of these limitations, the usage of Xiao’erjing was limited to those who couldn’t read and write Chinese Hanzi characters. Those who could write Hanzi characters preferred to write Hanzi.

In the modern era, with the emergence of several Chinese transcription systems like the pinyin that this post uses, Xiao’erjing has largely fallen of use. However, I believe that Xiao’erjing represents an important and unique piece of Chinese history and should be preserved. It shows a story of a Multicultural China, one where many different groups of people lived together peacefully, shared cultural practices with one another, and created a unique cultural identity in China.

A forgotten history

Literature about China’s Islamic history is sparse in both English and in Chinese. Political factors since the Qing Dynasty have led to the surpression of Islam in China and the segregation of Han, Hui, and other ethnic groups in modern history.

Most troubling is the brutal oppression of the Uighur people, the stoking of ethnic tensions between the Uighur and the Hui, and the destruction of Chinese Mosques.

But there is a decent amount of research and literature that already exists on Islamic Chinese topics.

Many people have expressed interest in this topic to me, but I regret that I am just a Computer Science student. But I’m working on curating some resources on Islamic China and the Silk Road, and I will be presenting and linking to some works by scholars who have studied this topic in my next post.

EDIT: But for now, Iskandar Ding, the author of the first image in this post, has coincidentally published a much better overview of Xiao’erjing the same day I published my post. Please check it out here: https://sinoarabica.com/2025/02/03/xiaoerjing-an-introduction/

Leave a Reply